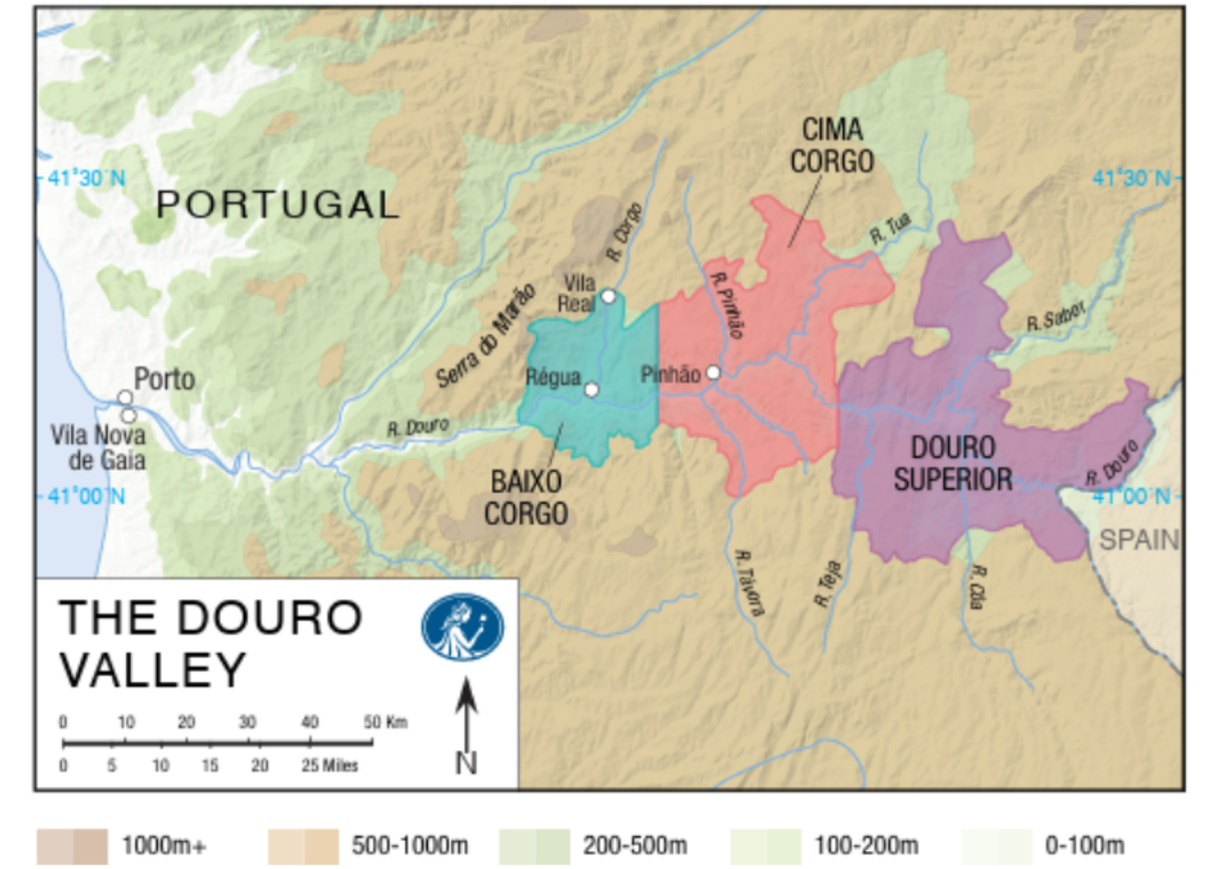

The Douro Valley, the birthplace of Port, is a UNESCO World Heritage landscape carved into steep, schistous slopes that track the River Douro across northern Portugal. Although Port is one category, the Douro is not one uniform place. It’s a patchwork of subregions – Baixo Corgo, Cima Corgo and Douro Superior – each with their own climate, topography and viticultural challenges. Understanding these ‘regions within the region’ is one of the quickest ways to understand why Port tastes the way it does.

Looking for an introduction to Port? Check out this webinar recording.

It’s all about the schist

The Douro region stretches across north-east Portugal. It covers around 250,000 hectares, though only about 41,000 are planted with vines and 33,000 are registered for Port (DO Porto). This is a land of extremes: summers can reach 40°C, while winter frosts are not unusual. The valley lies about 70 km from the Atlantic Ocean, but the Marão mountains shelter it from cooling coastal winds, making it hotter and drier than the city of Porto on the coast.

Vineyards run along the River Douro and its many tributaries, rising from around 150 to 900 metres above sea level. This varied landscape means that even neighbouring plots can experience different temperatures and levels of sunlight.

Beneath the surface, the soils are thin, stony and poor in nutrients, but the underlying rock - schist - is crucial. Schist breaks into vertical layers that allow vine roots to push deep underground in search of scarce water, which is essential in this hot, dry region. The official boundary of the Port demarcation largely follows where schist is found, since the neighbouring granite bedrock holds water poorly and is much less suitable for vines.

Three subregions, three expressions

Baixo Corgo: cooler, wetter, earlier-drinking

The westernmost zone is also the coolest and wettest, with around 900 mm of annual rainfall. Proximity to the ocean and the shielding effect of the Marão mountains are both felt a little less here than further inland. Elevations and north-facing slopes add further moderation.

Grapes here tend to ripen less fully than in the central and eastern Douro, so wines are typically lighter in body and concentration. Fruit from Baixo Corgo often channels into inexpensive Ruby and Tawny Ports, where a fresher, simpler fruit profile is ideal. Viticultural pressure is higher: downy mildew and botrytis are more frequent, and spring frosts can bite at higher sites. Careful canopy management, fungicide programmes and site selection (e.g., avoiding the coolest, shadiest pockets for early-ripening, disease-prone varieties) all help growers meet style and quality targets.

Cima Corgo: the heartland of classic Port

Head further east and you reach Cima Corgo, with less rain (about 700 mm annually) and a warmer, drier climate. This central zone is home to many of the Douro’s most famous quintas and is regarded as the beating heart of quality Port production.

In the glass, Cima Corgo grapes form the backbone of age-indicated Tawny Ports and Vintage Ports. The conditions here give wines deep colour, firm tannins and ripe black-fruit and floral notes - the hallmarks of Port styles built for long ageing. It’s also where many shippers define their house style, blending across sites and aspects to achieve consistency year after year.

Douro Superior: hotter, drier, powerful

Finally, the valley opens out towards Spain in the Douro Superior. This is the hottest and driest subregion, with only 450 mm of rainfall in an average year. Summers can be extreme, drought is a frequent issue, and the climate is far more continental than the zones closer to the Atlantic.

When water stress is managed, Douro Superior produces full-bodied, powerful wines that are increasingly important for both top-end Ports and still Douro DOC wines. Unlike the steep, terraced vineyards further west, parts of this area have flatter land that allows mechanisation, so new plantings are on the rise. Grape variety choice and rootstocks are critical here: Touriga Franca and Touriga Nacional cope well with heat, while drought-tolerant rootstocks are commonly used.

Shaped by the slopes

Everywhere you look in the Douro, the valley’s steep hillsides dictate how vines are planted. The most traditional layout is the socalcos, narrow terraces held in place by dry stone walls. They wind up the hillsides like steps, creating a dramatic landscape that is now protected by UNESCO. Socalcos allow for high planting densities, but they require constant upkeep and can only be worked by hand, making them expensive and labour-intensive.

From the mid-20th century, growers started to build patamares, terraces supported by earth banks instead of stone. These are wider and cheaper to maintain, and crucially they can be accessed by small tractors. Modern single-row patamares are even shaped with a slight inward tilt, designed to hold rainwater for longer and to reduce erosion on these dry, hot slopes.

On gentler gradients, you may see vinha ao alto, with vines planted in straight lines running up and down the hill. This approach is more land-efficient and allows for mechanisation, but it also increases the risk of water run-off and soil erosion.

Beyond the terraces themselves, vineyard management in the Douro is highly pragmatic. Vines may be cordon-trained and spur-pruned, or head-trained and cane-pruned, but in both cases vertical shoot positioning (VSP) is common. This system helps growers manage sun exposure and makes mechanisation possible where the terrain allows.

Yields are naturally limited by the combination of heat and scarce water. The legal maximum for Port production is 55 hL/ha, but in practice many vineyards produce closer to 30 hL/ha. The challenges differ across the valley: in the wetter west (Baixo Corgo), growers have to contend with downy mildew, botrytis and the risk of spring frosts, while in the hotter east (Douro Superior), the focus is on managing drought and heat stress.

Even before the grapes reach the winery, these choices are already shaping the style and quality of the Ports that emerge from the Douro.

From vineyard to style

One of the defining features of Port is that fermentation is stopped early by adding spirit. This means winemakers must extract colour, flavour and tannin quickly before fortification brings the process to a halt. The traditional method is foot treading in granite lagares, shallow tanks where teams tread grapes to crush the grapes. It is still considered the benchmark for thorough yet gentle extraction. Today, many wineries use robotic lagares, which replicate the process without the need for large seasonal crews. Other techniques, such as pumping over, stainless-steel pistons or autovinifiers, provide alternatives that can be matched to the intended style, whether that is a lighter Ruby or a Vintage Port built for decades of ageing.

While winemaking choices are important, the starting point is always the vineyard. Fruit from Baixo Corgo often suits early-drinking Ruby and Tawny Ports, where freshness is most valued. Cima Corgo provides the backbone for Vintage and age-indicated Tawny Ports, delivering the depth and balance required for long maturation. Douro Superior, with its heat and intensity, contributes the power and concentration that define some of the valley’s boldest Ports and increasingly its still Douro DOC wines.

Most Ports are blends of vineyard parcels, grape varieties and sometimes even vintages. Blending helps producers maintain a consistent house style. Yet once you know the valley, the imprint of place becomes easier to recognise in the glass.

How to spot it on a bottle

You won’t usually see ‘Baixo Corgo,’ ‘Cima Corgo’ or ‘Douro Superior’ printed on a Port label. Producers traditionally blend across the valley, and the wine is simply labelled as ‘Port.’ But there are a few hints:

- The style gives it away. Everyday Ruby and Tawny Ports often include fruit from Baixo Corgo. Age-indicated Tawny and Vintage Ports are typically built on Cima Corgo fruit. Douro Superior is behind many of the most powerful Ports and a growing number of Douro DOC still wines.

- Look at the producer. Many famous quintas, like Quinta do Noval or Quinta do Bomfim, are based in the Cima Corgo. Knowing where a house has its vineyards can help you place the origin.

- Still Douro wines. For unfortified wines labelled ‘Douro DOC,’ subregions are sometimes named on the label, especially from Douro Superior.

So while the subregions are more a key to understanding Port than shopping for it, they can help you read between the lines of what’s in the bottle.

Further learning

This blog was inspired by the content covered in the WSET Level 4 Diploma in Wines. The Douro subregions are explored in detail in the textbook, and students are encouraged to link geography, climate and vineyard practices directly to the styles of Port in the glass.