Unlike most terms used for Italian wine, Super Tuscan has no fixed meaning and is not legally defined. If a bottle of wine is sold as Brunello di Montalcino, there are unambiguous rules about where the grapes must be grown, which variety can be used and how long the wine must be aged (and even in what sort of container). None of this applies to Super Tuscan.

But how did this term arise? And what does it mean for Tuscan wine?

David Way, author of The Wines of Piemonte and Senior Researcher and Curriculum Developer for the WSET Level 4 Diploma in Wines, investigates.

Back in the 1960s, Tuscany was awakening from slumber in terms of wine quality. Much of the wine made was of a very basic quality. Large bottling companies bought huge volumes of grapes and wine from farmers at the lowest possible price. The dominant red wine was made from a blend of red and white grape varieties: pale in the glass, very acidic and lacking well-defined fruit character. The bottlers would regularly buy deeper coloured and more alcoholic wines from the south of Italy and blend them to improve the local wines. Fraud was common.

A wider economic boom was taking place in the country after the Second World War, and the wine sector desperately needed to modernise itself. The primary response was to introduce the DOC system (denominazione di origine controllata, or protected denomination of origin), which specified detailed rules designed to ensure quality and authenticity, in short, to raise the reputation of Italian wine.

Tuscany's early development

In Tuscany, the largest and most well-known denomination that was introduced was Chianti DOC. As in Tuscany generally, Sangiovese was and remains the most planted grape variety. However, the rules of the DOC were very different to what they are today. They required Chianti DOC to be made with 50–80% Sangiovese, 10–30% Canaiolo Nero and 10–30% Trebbiano Toscano and/or Malvasia del Chianti and up to 5% unspecified complementary varieties.

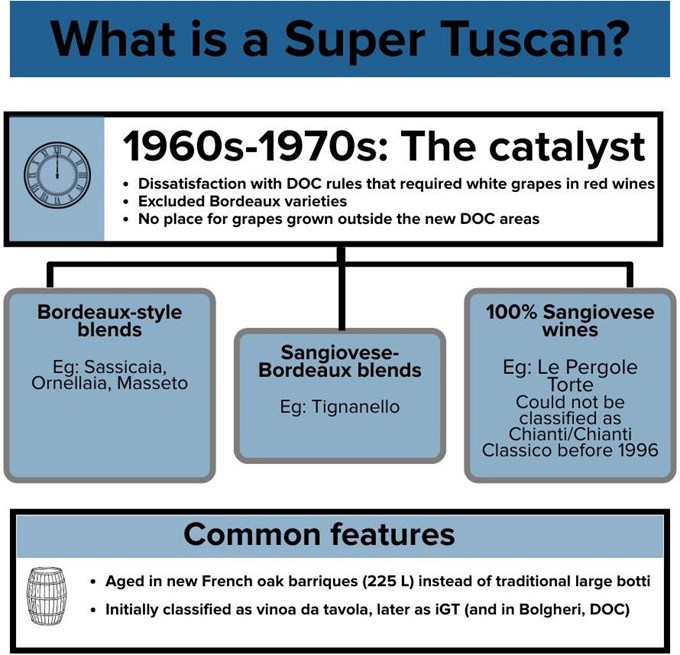

In short, the wines could not be 100% Sangiovese and had to include white grape varieties. The latter inevitably reduced the colour and flavour intensity of a red wine. These rules reflected the varieties that were planted in the vineyards back then and the need to make as much wine as possible from those vineyards. In summary, quantity over quality.

At the same time, ambitious Tuscan producers were beginning to experiment with non-native grape varieties. Aristocratic families enjoyed the wines of Bordeaux, and the adventurous were keen to try Cabernet Sauvignon, particularly in their own vineyards.

Cabernet Sauvignon

The most famous pioneer who launched Sassicaia had land in Bolgheri on the Tuscan coast, a long way from Chianti and famous for racehorses rather than for wine. In terms of winemaking, the Bordeaux-influenced enologist, Giacomo Tachis, employed by the Antinori family, was a champion of the barrique, just 225 litres in capacity and made of toasted French oak. They helped to fix colour in red wines and softened tannins, while also adding vanilla and spice aromas to the wines. This was a very different ageing vessel from the old, large botti (casks) traditionally used in Tuscany, typically made of Slavonian oak or chestnut. At best, these 1,500 to 10,000 litre vessels were neutral maturing vessels; at worst, when not properly maintained, they added off flavours to the wines.

Breaking the rules

As a result of these parallel developments, ambitious or adventurous producers had no choice but to go outside of the emerging DOC system. The most famous to do so was Mario Incisa della Rocchetta, who settled in the then unknown village of Bolgheri. He planted Cabernet Sauvignon in 1944, initially in a one-hectare vineyard, and made wine for his family’s consumption. Through his connections with the Antinori family, he was persuaded by Giacomo Tachis to age the wine in barrique and, eventually, to put it on the market. The first commercial release of Sassicaia was in 1971 of the 1968 vintage, two decades after the first wines were made. In the same production year, San Felice made a wine, daringly, of 100 per cent Sangiovese, called Vigorello.

In 1975, Antinori created the modern version of Tignanello, a blend of 80 per cent Sangiovese and 20 per cent Cabernet Sauvignon. Though grown in the heart of Chianti Classico, it, like Sassicaia and Vigorello, had to be vino da tavola. The famous early wine critic, Luigi Veronelli, urged Antinori not to worry about the legal category but to name the wine after its Tignanello vineyard, again a revolutionary development.

Thus, long before the term Super Tuscan label was thought up, the three categories of Super Tuscan were present in the earliest years of these developments. Sassicaia was born as a Bordeaux blend grown in an area with no DOC; Vigorello then was 100% Tuscan, with grapes grown in Chianti, but could not be called Chianti; the grapes for Tignanello were grown in the heart of Chianti, but because of the use of Cabernet Sauvignon in the blend was also outside the Chianti regulations.

Sassicaia and Tignanello have gone on to be among the best-known Super Tuscans. And to complete the picture, over the decades, Vigorello has morphed into a Bordeaux-influenced wine, but nowadays, part of the blend has the rare Tuscan variety Pugnitello as a vital part of the mix. ‘Super Tuscan’ is truly a flexible category!

Sassicaia being poured at a wine tasting.

So, what is a Super Tuscan really?

In summary, the term Super Tuscan refers to red wines made in Tuscany which did not fit into the regulatory framework of Chianti DOC back in 1967. The reason they became so important was the ambition to create top-quality, even world-class wines, in contrast to the very average wines which had been common in the region. Hence Super Tuscan! The rest of the wine world took notice when Hugh Johnson organised a blind tasting in 1978, which included Bordeaux first growths and Sassicaia. The Tuscan wine was voted the best wine above its more famous Bordeaux cousins. Then the young Robert Parker awarded Sassicaia 1985 100 points, another testimony to its quality.

The 1970s and 1980s saw yet further developments. Montevertine’s 100 per cent Sangiovese wine, Le Pergole Torte, with fruit grown in the prime Chianti village of Radda, was rejected by the Chianti authorities. The wine was released as vino da tavola in 1977 and became a cult wine treasured by enthusiasts and collectors. Ornellaia released its first Bordeaux-inspired wine in 1985. The company followed with its pure Merlot, Masseto, from 1986.

Wine law eventually caught up with the outstanding wines being created. The IGT category (Indicazione geografica tipica, protected geographical indication), elsewhere in Italy, the category for less prestigious wines, became the home of the Super Tuscans from 1992. Bolgheri became a DOC in 1994 for Bordeaux blends and, finally, in 1996, Chianti changed its rules to make white grapes optional and allow 100 per cent Sangiovese wines.

While the term Super Tuscan cannot be defined simply, we can say that there are basically three main types of wine under this designation: Bordeaux blends (though more recently producers have also made use of Syrah), Sangiovese-dominant wines in which the blending partner is a Bordeaux variety and some highly regarded pure Sangiovese wines. A further common feature is the use of French oak barriques to age the wines.

The term itself was probably first used in print in 1985 by the British wine importer and journalist, Nicolas Belfrage. More importantly, these wines were the result of the ambition of Italian winemakers to produce wines that were of the same quality level as the top wines from around the world. This had a profound influence on the ambition of quality-minded growers across the whole of Italy. In a couple of decades, the move had been made from bulk wine of no distinction to wines that are lauded around the world.